Effective content chunking for vector embedding large text documents

Every piece of written content inside Storyden, be it a post, a page, a submission or a reply, flows through a single system: the Content type. It’s not just a blob of HTML. It’s a full-featured data structure that’s aware of links, references, summaries and chunks. And all of this is essential for ergonomic APIs as well as helping language models work well with the data.

Whether you’re building a recommendation engine, semantic search, or adding context-aware responses, you’ll need to treat raw content as more than just a string. This post explores how Storyden approaches this challenge, and why it does things the way it does.

Text Is Not Enough

A lot of content systems store HTML in a database. WordPress does this, and so does Storyden. HTML is portable, standardised and very well understood. However, on its journey from fingers to file, Storyden does a bunch of processing to better understand the actual content structure to do some useful stuff with it.

This "useful stuff" facilitates features like:

- Sanitise, because you can't trust the client, XSS is still a thing!

- Run semantic search (though I'm still skeptical of how useful this is...)

- Summarize content for previews, cards,

<title>, opengraph, etc. - Detect both external and internal links

- Generate embeddings for an LLM to use in Retrieval-Augmented Generation

Sanitisation: Safety first

Before anything else, raw input is passed through a sanitiser. This strips out unsafe tags or attributes, but still allows the Storyden-specific URI scheme, sdr: which are internal reference links between pages, posts, members and more (you can read more about that here!)

This approach lets members write, POST or paste rich content (even from suspicious sources) without worrying about <script> tags, malicious inline styles, onclick, etc.

Structure over noise

After sanitising, the content is parsed into a structured tree via Go's html package. This isn't used for rendering or changing the content, but it is useful for extracting things like:

- External links: external URLs so that Storyden can index them in the Link Aggregator

- Internal links, or "references":

sdr:URIs (e.g.sdr://thread/xyz123) - Media: image sources (and maybe videos one day? 👀)

- Plaintext: the raw text content, useful for LLM-based summarisation (another thing I’m skeptical about in terms of usefulness, tbh)

- Short Summary: a preview-friendly summary, capped at ~128 characters

- Chunks: pieces of text with loosely defined boundaries

Chunking

or: why you clicked this post in the first place probably.

One of the most important things the Content type does is chunking: breaking large blocks of text into smaller, semantically coherent units.

Why do this?

Firstly, large language models operate within context limits and when you want to run inference using a piece of content, it's not always desirable to put the entire piece of content into the context window. Sometimes this is useful, like when I finish this post I might paste the entire thing into a GPT to proof-read it. But for other use-cases it's not going to yield the best results.

Secondly, and probably more importantly, the coordinates you get from vector embeddings become less and less localised the larger the text is. This isn't always the case technically, if you write 10 paragraphs about how cats enjoy laying in the sun, it will probably localise fairly well to a specific region in vector space. But people don't write like that. Forum users and directory curators don't write like that. Human writing bounces around, starting in one place and ending somewhere else.

So because semantic meaning matters, chunking needs to be aware of a few requirements:

- Chunk boundaries cannot be mid-sentence

- Chunks must be small enough to represent a fairly self contained unit of meaning.

- However, leniency must be allowed for longer spans of text, because it's humans behind the keyboard and humans are creative!

How does it work

Storyden uses a hybrid approach to chunking, first breaking down high level then going per-paragraph to split further.

First, it walks the HTML tree for paragraph-style elements like <p>, <h2>, <blockquote>, etc. to get a list of root level blocks, think paragraphs, headings, code blocks, quotes, etc.

func (c Content) Split() []string {

r := []html.Node{}

// first, walk the tree for the top-most block-content nodes.

var walk func(n *html.Node)

walk = func(n *html.Node) {

if n.Type == html.ElementNode {

if /* omitted for brevity: n.DataAtom is a top-level block element */ {

r = append(r, *n)

return // return, as we don't want to recurse into the tree.

}

} else if n.Type == html.TextNode {

r = append(r, *n)

}

for c := n.FirstChild; c != nil; c = c.NextSibling {

walk(c)

}

}

walk(c.html)

chunks := chunksFromNodes(r, roughMaxSentenceSize)

return chunks

}Then, chunksFromNodes recursively splits them again down to a rough sentence-size boundary (roughMaxSentenceSize which is 350 characters, based on research of the English language*). Boundaries are currently English/Latin-based only*, using basic terminal-punctuation (periods, exclamation, question, etc.)

* yes this is all English or European-latin only currently, see the conclusion for discussion and further research.

func chunksFromNodes(ns []html.Node, max int) []string {

chunks := []string{}

for _, n := range ns {

t := textfromnode(&n)

if len(t) > max {

chunks = append(chunks, splitearly(t, max)...)

} else {

chunks = append(chunks, t)

}

}

return chunks

}The core paragraph-level splitting is done in splitearly, which is applied when the first-pass chunk is too long (true in most cases.)

Leniency is applied by doubling the boundary (700 characters) and walking down until a punctuation boundary is found, this allows for larger chunks if someone wrote a very long paragraph.

In a worst case scenario (no boundaries were found, maybe you're discussing very long chenical names?) the last found space is used, or failing that, the upper boundary at position 700.

func splitearly(in string, max int) []string {

var chunks []string

var split func(s string)

split = func(s string) {

if len(s) <= max {

chunks = append(chunks, strings.TrimSpace(s))

return

}

upper := min(len(s), max) - 1

if upper == -1 {

// reached end of input stream

return

}

lower := upper / 2

boundary := upper

fallback := -1

outer:

for ; boundary > lower; boundary-- {

c := s[boundary]

switch c {

// very rudimentary sentence boundaries (latin only at the moment)

case '.', ';', '!', '?':

break outer

// worst case: no boundaries found, use the closest space

case ' ':

if fallback == -1 {

fallback = boundary

}

}

}

if boundary <= lower {

if fallback > -1 {

// worst case: no sent boundaries, split at fallback position.

boundary = fallback

} else {

// worst case: no fallback either (the input string was a solid

// block of text with no spaces or sentence boundaries.)

boundary = upper

}

}

left := strings.TrimSpace(s[:boundary])

right := strings.TrimSpace(s[boundary+1:])

chunks = append(chunks, left)

if len(right) > 0 {

split(right)

}

}

split(in)

return chunks

}The result is a list of pretty well-formed, meaningful text chunks which are now close to perfect for vector embedding. For example, this very post that you're reading, when run through the chunking algorithm, yields these first 5 chunks:

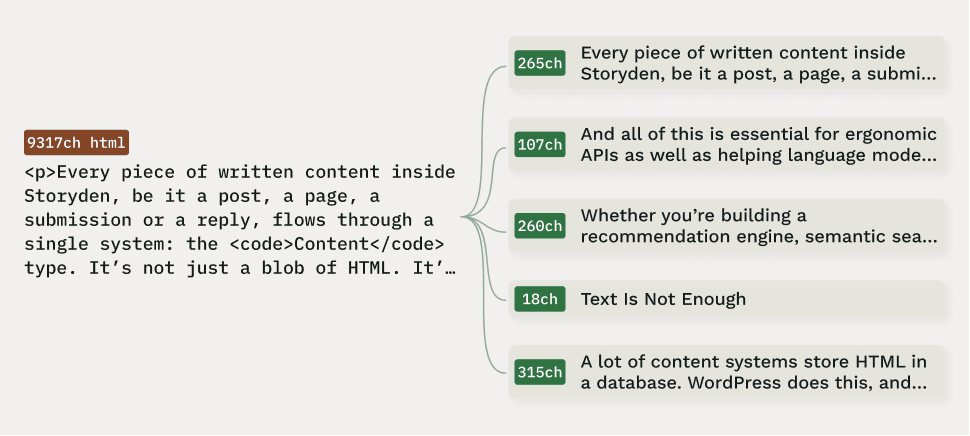

Every piece of written content inside Storyden, be it a post, a page, a submission or a reply, flows through a single system: the Content type. It’s not just a blob of HTML. It’s a full-featured data structure that’s aware of links, references, summaries and chunksAnd all of this is essential for ergonomic APIs as well as helping language models work well with the data.Whether you’re building a recommendation engine, semantic search, or adding context-aware responses, you’ll need to treat raw content as more than just a string. This post explores how Storyden approaches this challenge, and why it does things the way it does.(Note, this heading is probably not a useful extraction of semantic value now that I think about it... to resolve this, I'd remove headings from that initial rood element gathering step at the start.)

Text Is Not EnoughA lot of content systems store HTML in a database. WordPress does this, and so does Storyden. HTML is portable, standardised and very well understood. However, on its journey from fingers to file, Storyden does a bunch of processing to better understand the actual content structure to do some useful stuff with it.This means when you ask a question or use other LLM-powered features on Storyden, it can search the coordinates of each paragraph of each post or page, rather than the much more vague and "averaged" embedding of entire documents.

Designed for RAG, but useful elsewhere

A lot of modern RAG systems use chunking, with various different algorithms (though, at the time of building this in 2023/2024 there were not a lot of resources available on the topic discussing different approaches, especially for rich HTML trees.)

And while chunking is primarily done for semantic search (almost useless) and Retrieval-Augmented Generation (boring), it has knock-on benefits across Storyden:

- Summary descriptions: for OpenGraph cards and

<title>tags. - Recommendations: Embedding at a more granular level allows more sophisticated recommendation algorithms.

- Filtering: when building context for a prompt, you can more easily discard irrelevant chunks using metadata.

What about internationalisation?

In short, it's hard. I'm an NLP nerd and I wrote my thesis on it while working for a company doing lots of NLP analysis of Ministry of Defence documents, it was hard back then with just English and we used tools like SpaCy. Language models do make some things easier but there still exists the fundamental problem of data pre-processing. Which is key to training models, and sometimes even necessary when using models like GPTs.

Much of NLP at that time was very procedural, using dictionaries and lookup tables of word types, stopwords, stemming, sentence-splitting, etc. I'm not sure how the industry has changed now but at that time, it was very manual in terms of procedural code running over text. There aren't many tricks you can use with language, especially English. Languages are messy, a product of ever evolving cultures with new words, grammatical structures, cases, slang and other elements popping up all the time. What I've done here may work with some European languages but it definitely not work as well with Persian, Arabic, Korean, Urdu, etc.

The challenge isn't just in the boundary markers, sentence size and characters. It can go deeper, for example some languages don’t use spaces to separate words at all, even the concepts of “paragraph” and “sentence” aren’t universal. And then there are languages like German, somewhat fusional/agglutinated, where a single sentence can contain what feels like an entire essay thanks to compound nouns and nested clauses. Or fully agglutinated languages like Turkish.

A solution that's multi-language would probably need to be a lot more declarative and less procedural.

Tasty chocolate chunks

This whole system might seem like a lot of complexity but language models are no different to classic artificial intelligence or NLP: your success depends on the quality of the input data. Chunking in such a way that's somewhat semantically aware of the structure (not hard-cutting mid sentence, etc) yields better results in the (very informal and unscientific) benchmarks I've run.

It also turns out splitting HTML is quite complex due to the different element types, leniency of HTML itself, and also just because the Go html.Node type is hella awkward to work with (but very powerful!)

If you’ve got a forum, directory, wiki, or anything that revolves around lots of human-written content, and you want to add actual intelligence on top of it, this approach will get you far.

You can try this out right now:

docker run -p 8000:8000 ghcr.io/southclaws/storydenOr check the getting started documentation. Note: in order to enable LLM features (they are aggressively opt-in, as it's not for everyone) you must enable the Semdex (semantic index) by:

- providing a vector database - for quick testing you can use Storyden's embedded vector database, Chromem (read more)

- providing a language model - for now, OpenAI is the only supported provider (read more)

If you're interested in checking out how it works, you can read the code and tests on GitHub.

I hope this article was helpful, spread the word if you enjoyed it!

Back to index